Today, crowds stream through the doors of Ultra Suede at 661 N. Robertson Dr. near Santa Monica and dance the floors of The Factory at 652 N. La Peer Dr. Both entrances are to a single building that West Hollywood knows simply as The Factory. But before it became known for manufacturing ecstatic nightlife, The Factory was an actual factory and used for a number of other things.

The building is a simple box with two small branches, one at Robertson and one in the middle. It is split into multiple floors on the inside and is basic, big, open and raw. It fronts on two streets with entrances on all sides, an unusual feature that has helped it remain viable through the years. That’s because this huge building with its blank exterior can be divided into a jigsaw puzzle of independent spaces and never needs to commit to being just one big thing.

This chopped up quality makes piecing together its story more complex. Parts of the building come alive and others die off independently of the others. Uses overlap, and hiding in every corner are rumors of what might have gone on. Some of these rumors are true, while others are fabrications accepted by many as common knowledge.

The Mitchell Camera Company built The Factory in 1929 to manufacture motion picture cameras. Mitchell cameras were the workhorses of Hollywood studios for decades. The company was owned by a Chicago group with Williams Fox, namesake of the Fox entertainment empire, holding a 50 percent stake. Mitchell Camera thus found itself in the middle of many of Fox’s legal and territorial battles with other studios and manufacturers.

Mitchell’s cameras were so popular that the company decided to increase its production capacity, adding a wing to its Robertson Boulevard factory in February 1941 that extended it to La Peer Drive on the opposite side of the block. In December of that year the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II. Much of the country’s manufacturing resources were adapted to the war effort and some believe the Mitchell Camera factory was reconfigured to produce the notorious Norden bombsight.

One of the most closely guarded secrets of World War II and the most expensive after the Manhattan Project, a Norden was the bombsight used on the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the atomic bomb that annihilated Hiroshima. By 1945 the production of Norden bombsights was stopped, superseded by more accurate radar technologies.

It has been difficult to locate any evidence that Norden bombsights were produced at The Factory. Members of the Norden Retirees Club identified New York and Connecticut as the primary manufacturing areas and raised doubt about a West Hollywood bombsight factory. The timeline and context does not rule out the possibility, but the idea that Norden bombsights were manufactured in West Hollywood remains little more than rumor.

Mitchell Camera decided to move to Glendale after the war in 1946. The West Hollywood factory then became the Veteran Salvage Depot, a processor of military salvage. There is little on record about this facility, but it made the LA Times in 1951 when a fire damaged it and adjacent factories. The building subsequently became a furniture factory but was abandoned sometime in the 1960s.

In 1967 the factory finally said goodbye to its life as a factory proper and became “The Factory,” a buzzing center of the Los Angeles club scene.

Turning the abandoned furniture factory into a nightclub was the brainchild of Ron Buck, a lawyer, architect and artist who bought the space in 1967 and transformed it into the most exclusive of invitation-only nightclubs. His investors, also club regulars, included Hollywood director Dick Donner (of “Salt and Pepper,” “Superman,” “Lethal Weapon” and “The Goonies”), Peter Lawford (of the Rat Pack), Anthony Newley, Paul Newman, Peter Bren, Jerry Orbach and Pierre Salinger. Some believe The Factory was owned by Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack, but a 1967 LA Times article titled “Swinging Shift Runs The Factory” clearly describes it as Buck’s venture and lists his investors with no mention of Sinatra or the Rat Pack beyond Lawford, whose presence likely sparked the rumor.

With its multiple stages of live entertainment, a gourmet restaurant and A-list guests, The Factory quickly became the place to be seen. Buck decorated the club with antiques and a sense of humor. The interior was a mash up of eras and pieces. Nineteenth century pool tables were racked next to antique barber chairs, rows of church pews knelt under crystal chandeliers and bronze Indian heads, wood paneling and leather club chairs added a worn gentlemanly vibe. The interior’s most spectacular feature, repurposed stained glass windows deployed as room dividers, gave the space a twinkling Tiffany sparkle.

The lower floor was converted into an art gallery when the club opened (presumably for Buck’s own work) and numerous businesses and uses of all kinds have carved out their own piece of the factory’s lower floors since. These include, among many others, the offices and manufacturing facility of the Hamilton-Howe furniture company, a collection of arts and crafts shops known as “The Street,” the temporary location of Koontz Hardware, a cabaret theatre called “The Backlot,” which hosted many famous names, various smaller clubs and more recently the Fitness Factory gym.

By 1972 the buzz around The Factory nightclub had waned, and it shut its doors. Potential tenants had difficulty re-opening the space as a nightclub, citing code compliance, health department and parking availability issues. It opened briefly as the “Paradise Ballroom” but, in trouble with county officials, it did not last long. But in 1973 The Factory took a dramatic spin, opening as “Spaghetti Village,” one of the cheesiest of family theme restaurants.

A Disney-like attempt at a literal Spaghetti Western (sans any of Sergio Leone’s talents) Spaghetti Village transformed the interior of the building into a faux street scape. Spaghetti with a choice of 10 different sauces for $2.95 was served in a stage-set-like Wild West jailhouse, fire station, general store and “other quaint settings.” Beer and wine was available in two old-time saloons, and the whole old-timey jumble was topped off with an antique boutique and penny arcade.

Spaghetti Village was gone within two years and the Wild West decor cleared out in 1975 to make room for Studio One, which was to be the hippest of nightspots.

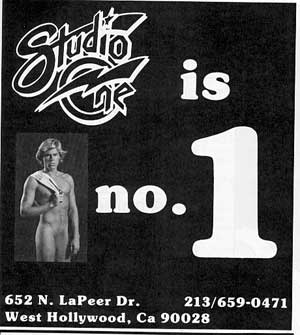

It was the height of the disco era, and West Hollywood’s gay community was large and visible. Studio One was conceived specifically for this set and offered no shortage of mirrored balls (seven to be exact), strobe lights, lasers, a gleaming red neon Pegasus and a fish tank in the men’s room that spouted water for hand washing—though the round sink under the aquarium was often mistaken for a circular communal urinal, a show of its own. Studio One also boasted a party yacht called Pegasus moored in Marina Del Rey. A strutting pinnacle of disco flash, Studio One was consistently packed with celebrities, models and only the sexiest of men.

The club was owned by Scott Forbes, an optometrist to the stars turned party promoter. Forbes had a clear vision for Studio One and quoted in an LA Times interview describes it as being “planned, designed and conceived for gay people, gay male people. Any straight people here are guests of the gay community. This is gay!” With a dance floor that boasted a capacity of 1,000, Studio One was open seven days a week and was constantly packed.

But Studio One was not only a club, it also hosted benefits and events and began a number of traditions that are still alive today. For example, Forbes felt that Disneyland would be a great place for a gay party. He booked the park in the name of the Los Angeles Bar and Restaurant Association without telling Disney that the majority of association members were gay.

“Once we had the contract signed I invited them to Studio One. That was a little shock for them,” he recalled. The event was a huge success, with 18,000 showing up at Disneyland for the party in 1978. The idea was expanded with trips to Magic Mountain and Knotts Berry Farm. The tradition continues to this day as ‘Gay Days.’”

It was during its life as Studio One that The Factory building received historic landmark designation in 1978. It eventually closed in 1988. After this the factory continued to be a club, but took a turn back to its classic nightclub roots when it was bought by lesbian entertainer Linda Gerard. She rechristened it The Rose Tattoo, presumably after the Tennessee Williams play of the same name. The Rose Tattoo was a celebrity filled cabaret, restaurant and piano bar where, as emcee, Gerard would open the evening’s entertainment with a song. In a room swathed with green carpet, mirrored walls and pink tinted art-deco bas-relief, jazz singers and a menagerie of performers crooned away on its many stages.

In 1993, citing exhaustion, Gerard closed The Rose Tattoo and sought out a less stressful entertainment career in Palm Springs, where she still entertains today. At this point the factory passed into the hands of another influential lesbian proprietress, Sandy Sachs. Sachs refurbished The Factory as a dance club, and over the next few decades made it one of the most successful and varied venues in West Hollywood, catering to crowds of all kinds. She sold The Factory in 2010, but it continues to be one of the most successful venues in town with numerous performances, packed club nights and other events.

This big box has had a long and varied life and shows no signs of slowing down. Its caverns are still chopped into useful size pieces and reconfigured whenever the next big thing wants to take a shot. New ideas are constantly coming and going. The bland exterior may rarely change, but with a rich and malleable inner world, The Factory is perhaps West Hollywood’s most dynamic and lively building.

Correction: A previous version of this story stated that the Factory served as the original location of Koontz Hardware. While Koontz was temporarily housed at the Factory, it was not the original location for the hardware store.

I was a regular at Studio One, The Rose Tattoo and The Backlot. I was 21 in 1976, I grew up in L.A. and feel very thankful. My friend, Mara Getz, see her on YouTube was a regular performer and there was room standing only when she performed there or the Backlot. I also had dinner at the vey chic Rose Tattoo restaurant. I miss this place very much. Mara lives in Palm Desert and is still available to book for events. If you were a gay man, you would hopefully be lucky enough to dine at Numbers Restaurant on… Read more »

Quick question. I was wondering if anyone reading this would know where the picture in the above article of the Backlot Theater came from? It’s the one with the cutout of Lorna Luft on stage.

Everyone’s an expert. What a fun comments thread, Marys.

Cherry by Bryan Rabin at the Love Lounge in the 90s was THE best party of the time. Unforgettable.

@vincent Tozzi is correct. Indeed The Factory opened in the summer of ’67. The address listed as 662 North La Peer Drive.

One of the owners, Ronnie Buck was friends with Jack Hanson. Hanson (founder of Jax stores) ran the popular, private club The Daisy, in Beverly Hills.

By ’71, The Factory was hosting live music and theater; ‘Feiffer’s People’ was performed there in ’71, and featured John Ritter..

I was about to write a timeline for the building when I happened upon this article which is accurate except that The Studio One Backlot was never on the first floor as it occupied the space that was later known as Ultra Suede. Linda Gerard eventually owned The Rose Tattoo but the Tattoo was in the building north of the main metal building. Sadly Linda Gerard passed away in 2014. I do remember someone telling me about the Paradise Ballroom being there for a short while and that Scott Forbes initially produced dance parties there and eventually bought the business… Read more »

The Rose Tattoo was not The Factory or Studio One, it was down stairs. I worked at Studio One and The Rose Tattoo at the same time.

When I worked at The Rose Tattoo 83-86 it was owned by Michelle, who later owned Le Dome. He Sold it to Ed Adammie (spelling?) .Pam and Linda bought it from him.

You forgot one era pre Studio One Disco whe it was The Paradise Ballroom http://www.discomusic.com/clubs-more/14736_0_6_0_C/

Unfortunately terri, that is not true.

We are trying to save The Factory – Studio One building from demolition. For info and updates, please see: https://www.facebook.com/savethefactorywesthollywood?ref=hl

***History and facts will help save the The Factory – Studio One building – if you have contacts, photos, info, etc to share regarding Mitchell Camera – The Factory – Studio One, please contact us at [email protected]

Thanks for the informative article, and to everyone for the comments. In the early 90s, I went to the Hollywood Boys Club, via the entrance on LaPeer. I used to have a plastic membership card.

The original writer really needs to correct so many errors in the article as others have pointed out. The whole 90’s history is pretty wrong. Studio One continued to exist far long than the writer claimed, and as others said, because Axis, then the Factory. And the Robertson side was Backlot to Love Lounge to Ultra Suede. I’ve been to and been involved in promotions at both the La Peer & Robertson venues since the early 90s, often on an almost weekly basis. I guess the writer was not around back then and didn’t check his facts well. Luna Park… Read more »

I always wondered why there wasn’t more chat about The Factory owned by Ron Buck, Peter Lawford and the others. I worked there as a bartender/waiter. When I went for the interview, Michael Carter, the hiring Manager told me that he was ordered to hire 40 “groovy” looking servers. He was told, “They can come from a modeling agency.” Our work outfits were bell bottom blue jeans, light blue jail shirts, red bandanas tied around our neck, white tennis shoes and white socks. At each plate setting was a silver metal liner with Factory written on it. The “F” was… Read more »