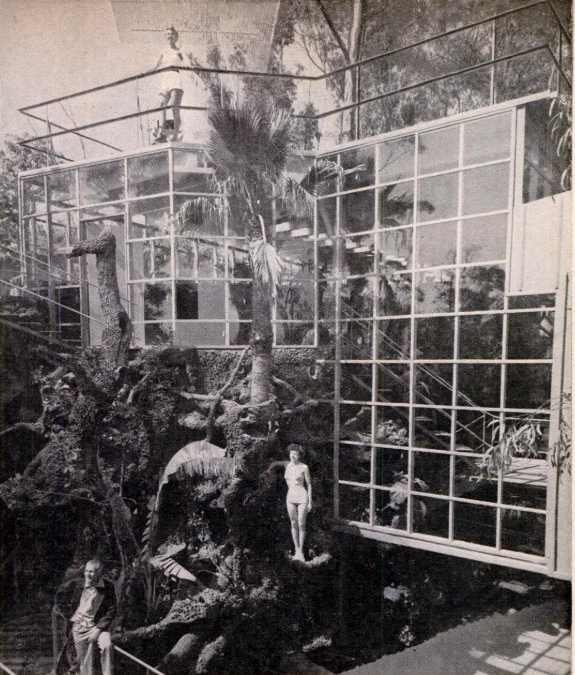

When attending an engagement at the home of Hal Braxton Hayes in the hills above West Hollywood, one entered through the orchid grotto — a multi-story, glass-walled atrium, with the stairs carved into an artificial coral cliff of spray-applied “Gunite” fireproof concrete.

A quick look back at your car would show you that it was parked on metal rails that slid out to cantilever over the side of a mountain-supporting retaining wall. It hung over the steep driveway that connects to Sierra Alta Way below—a “space-saving measure.”

The stair led up and out of the orchids, through a lush canyon of dense jungle-like foliage. The stair was flanked by two large and aggressively twisted statues (representations of war and death) that had been sculpted in the same rough concrete by the owner himself.

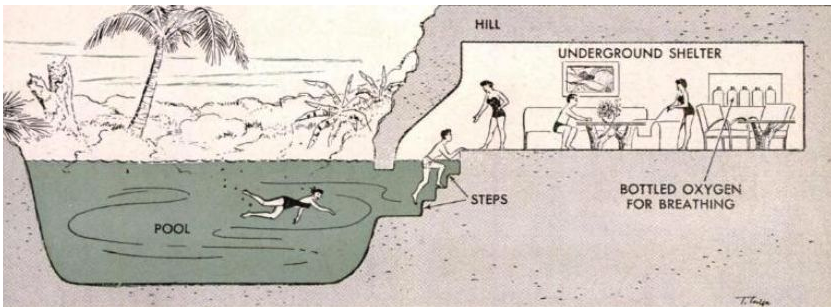

At the next plateau, there was an artificial sandy beach, with a pool, palm trees and topless starlets sunbathing. Just visible under the surface of the water there was a tunnel. Swimming through to the tunnel, you would emerge in a bombproof hideaway, stocked with food, drinking water and oxygen tanks.

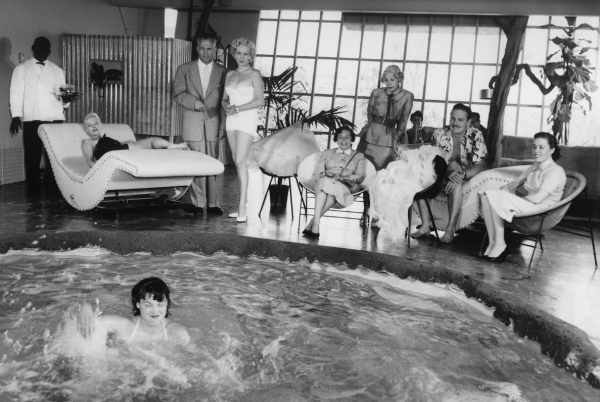

The beach-banked pool extended into the living room of the house itself (the underwater escape route always accessible), as did the jungle. The branches of one particularly large tree reached up through the roof and, by way of a painful-looking graft, a television protruded from the trunk. The lighting was all voice activated, and at the bar, built-in faucets dispensed scotch, bourbon and champagne.

The living room floor was covered by a heavy green shag carpet, one edge of which was tied to the wall. Following the cable up with your eye you would spot the winches that, with the push of a button, slid the carpet up to cover the windows—blocking flying glass and, according to the owner, the “gamma rays and neutrons” that would bombard the house after a nuclear blast in Los Angeles.

Finished in 1953, the house was a congealed mess of gimmicks, tricks of technology, Bond villain luxuries and “safety features” that make sense only to one with a profoundly paranoid mind and an overflowing bank account. Hayes, the home’s owner, designer and builder, was just such a man. He expected an imminent nuclear attack on the United States and outfitted his home accordingly.

An eccentric playboy, Hayes made his fortune as a builder, milking lucrative military housing contracts, and 1953 was the height of Hayes’ career. The house cost him $600,000 to erect—adjusted to today’s dollars, that’s $4.9 million. Time magazine called him “the founder and sole proprietor of what he claims is the world’s largest individually owned construction company.”

The qualifier “claims” is important. Even at his height, people recognized that Hays had a big ego and talked a big talk.

He portrayed himself as an expert in the field of nuclear preparation through architecture and building practices, claiming that the government regularly sought his input. However, accounts from military spokespeople and subsequent court cases make the reality of this claims dubious.

When it came down to it Hal B. Hayes was a high functioning nuclear paranoid, one able to spin his fears, quirks and ego as expertise and in the process make a lot of money.

So confident was Hayes in the ability of his houses to safely survive a nuclear blast that he proposed to build and reside in one at a Nevada nuclear test site … during a bomb test! The government quickly dismissed the idea, stating that “No human being can be permitted to jeopardize his life as a guinea pig, no matter how confident he may be.” Hayes responded that they were “Nuts! I would have been perfectly safe, I just want to show people in civil defense how it ought to be done.”

Hayes proposed whole communities of such nuclear-prepared homes, but despite this confidence, few were willing to invest. So while he continued to work on contracts for basic military housing, his nuclear preparedness innovations went into his own home.

Hayes, however, was in trouble not long after his home was finished. He had borrowed millions in low-interest loans in the early 1950s under the federal Capehart Act, which had been passed to boost home construction post-war. The loans came due, and Hayes was delinquent and had not delivered the housing units he had promised. Instead of building homes for military bases, he had built a home for himself and lived a lavish Hollywood playboy lifestyle.

Hayes’s trial was as dramatic as it was public, including Hayes’ flight to Mexico, his refusal to return for “health reasons,” and the private investigators who followed him and his bombshell blonde “secretary” in the U.S. and Mexico. Hayes acted as his own lawyer after his first one was hospitalized and was threatened with contempt of court for offering a million dollars to a key witness and a court interview with Zsa Zsa Gabor (his one time fiancé) about her 20-carat engagement ring.

At the end, Hayes lost big. He paid $8 million to settle the suits, sold his home and assets, paid off his numerous debts and moved to Mexico in 1962. Hayes became an artist, living in a villa in Acapulco with a pet jaguar as his only companion and a creepy shrine-like collection of portrait snapshots, each of a starlet he had bedded, flanking his bedroom.

He tried his hand at building again in Mexico, starting a 21-story international club on the side of a cliff, but was forced to abandon the project by the local authorities, who feared an earthquake would send it toppling. He turned the shell into a gigantic art project, a globby mass of cars, pipes and concrete, an undertaking for which he became known as “el gringo loco.” He died in Mexico in 1993.

***

It’s easy to write off Hayes’ actions as paranoid folly and his house as a ridiculous boondoggle built with ill-gotten gains. But with the threat of nuclear annihilation again prominent in the public mind, how is one supposed to rationally react?

Even with the technology of the 1950s, there was little warning that a nuclear bomb was flying on a plane overhead and every indication that one was. Today it takes a nuclear-tipped ICBM about 40 minutes to get to the U.S. mainland from North Korea … not much time to react, if you even know it has been fired.

What are you to do when you don’t know when the destruction is coming, but you know that it will be absolute and the political climate tells you it could happen at any moment of any day?

In the 1950s the response was a bomb shelter. A concrete and steel box built into your home that could withstand the big blast. You hear the air warning siren, you run for your bunker. That was the Hal B. Hayes house of the 1950s. It had more bells and whistles and a wine cellar but was at its essence a bunker.

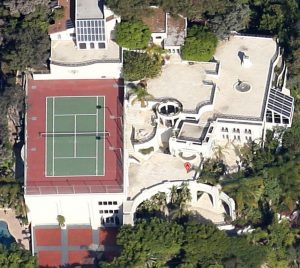

The Hayes house today, after changing hands multiple times and going through enough renovation in the 1970s and 90s to render it unrecognizable, takes a very different approach to the idea of risk and what is at stake in owning a home.

The house today is a totally banal vanilla cake mansion with enclosed and “usable” space and surfaces in a generic “luxury” non-style that has been dubbed the Villa Vendome Estate by Realtors. It follows a checklist that starts with marble countertops, ends with Greek statuary and can be completely and quantitatively accounted. Speculative design rolls downhill, and here it has followed the path of least resistance.

But, this genericness gives it a capability that the previous house, with all its eccentricities and technologies did not have, the ability to safely pass its value (today estimated at$22 million and rising) between owners without question or risk. The house doesn’t protect the body of the owner, but instead, his assets.

***

In the mid 2000s the Hal B. Hayes house was owned by basketball player Carlos Boozer of the Utah Jazz. He did not live there himself, instead renting it out for $70,000 a month.

When Boozer rented out the now 10-bedroom, 11-bath house to music legend Prince, it underwent a sudden and specific transformation that created a high profile tug-of-war. Prince took out a nine-month lease in 2005 and would end up being sued by Boozer for making extensive unauthorized changes to the structure during his short time there.

Prince had the exterior painted in purple stripes and added a Prince symbol and the numbers 3121 to the facade, a reference to his album that was coming out at the time. As promotion for the 3121 album, a private concert was to be held at the house. Invitations were Wonkaesque “Purple Tickets” hidden inside CD cases on store shelves. Inside the house, Prince brought in monogrammed black and purple carpet, had plumbing installed for a new in-house beauty salon and cut new openings between a number of rooms — more than what one typically does to a rental.

Why did Prince feel the need to totally customize a place he would be staying in for just a few months? In addition, why did Boozer become so upset that the changes had been made? He wasn’t going to be living there, was making $70,000 a month in rent and the Prince branding might have kept his tenant there longer or give it niche kitsch value.

It was a push and pull between two impulses: making something specific to oneself and making it generic enough that it could be anyone’s—a conflict ratcheted up by the incredible wealth of those involved.

The protection provided by the house today is in its speculative dollar value as opposed to the physical sheltering of the owner’s body, as the owner is likely never there. A perfect response to uncertain economic times and the risks that come with them. It works when, while a nuclear strike was certainly possible, it was not at all likely and thus not in mind.

Today this has changed. The possibility of being vaporized, the byproduct of a penis-measuring contest between petulant heads of state, feels far too real, imminent, urgent.

If any of Hayes’ original bunker survived the renovation, it could have become the house’s most important selling feature and, with an owner tied to the physical safety it provided, a less generic architecture could be in the house’s future.

Haye’s house has so far developed two responses to different types of annihilation, each reflecting the state of the times … at least for those with the money to do so.

A 2009 YouTube video shows what may have been the original bunker but now opened up and used as an indoor/outdoor space.

Interesting story.