EDITOR’S NOTE: West Hollywood in recent months has struggled with (and will continue to struggle with) issues such as protests over discrimination against people of color, the transformation of “Boystown” and the move of the annual LA Pride parade and festival out of the city. The city also is seeing its gay population (39% of WeHo residents in 2013 ) decline to 33% of residents in 2019. Don Kilhefner, a chronicler and creator of gay history, explains how we got to where we are today and fantasizes about where we may move in the future. It’s a lengthy essay, but compelling and insightful.

###

“Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.” Soren Kierkegaard

Los Angeles has been called “the cradle of American gay history.” It is unique among American cities in having a documented, somewhat organized, and sometimes visible presence for 70 continuous years beginning in the early 1950’s. This history has impacted the entire country.

Here’s the problem. These 70 years are usually looked upon as if they represent one undifferentiated continuity from one generation of struggle to the next. This is not true. This lack of historical under- standing has resulted in the current L.A. gay and lesbian establishment and ill-informed political correctees attempting to falsely rewrite or erase inconvenient parts of that gay history. What is occurring in L.A. is also happening, to a larger or smaller extent, throughout the country. Here are a few unconscionable and appalling examples in L.A.:

- WeHo Pride in 2019, on the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion, the very reason for Pride’s existence, completely ignored that earth-shaking event, pretending like it had never happened.

- The LA LGBT Center’s attempted in 2019 to falsely rewrite its early history and incorrectly cited 1969 as the date for its 50th anniversary celebration even though 1971 was the date used to commemorate its 25th anniversary.

- USC-ONE Archives refused to cooperate in an attempt to provide a venue to assess the impact of Stonewall on the development of the Los Angeles gay community.

- The vicious 1967 LAPD raid on the Black Cat, a Silver Lake gay bar, and its aftermath is skewed today to the point of misrepresentation, and there are other examples.

The question that needs to be asked is why this attempted rewriting of L.A. gay history is occurring? The answer is to be found in that history itself. Los Angeles gay history can be divided into four very distinct and vastly different periods.

The Mattachine Period (1951-1953): A Radical Beginning

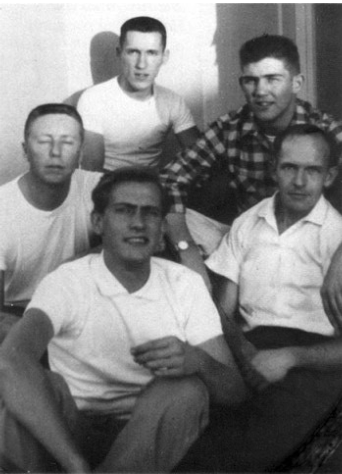

A national monument needs to be erected in L.A. to honor the seven men—Harry Hay, Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, Rudi Gernreich, Dale Jennings, James Gruber, Konrad Stevens—who responded to Hay’s original call for a homosexual organization that in 1951 became the Mattachine Society, named after the masked mattachini court jesters of medieval Europe thought by Hay to be largely homosexual men.

Mattachine represented the first successful attempt at organizing American gay men and lesbians and used their oppressor’s word, “homosexual,” to describe themselves.

Several of the men had been members of the Communist Party or other progressive organizations after World War II where they had learned organizing skills, analysis of social problems, and how to create a secret structure. Until the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion, protective super-paranoia based on individual safety and survival from hetero supremacists’ violence and physical and psychological genocide characterized homosexual reality.

The Mattachine is important for much more than just existing. For the first time in U.S. history, homosexuals identified themselves as an oppressed minority group, affirmed that there was such a thing as a homosexual culture, implied, but never actualized, collective political action, and organized successful, but secret, discussion groups entirely by word of mouth. In a pioneering and remarkable manner at that time, homosexuals began to dialogue with each other about their oppression as they experienced it—often cruel and deadly.

Mattachine was a top-down organization based on a secret organizational model of five levels that had been used by the fraternal Free Masons in 15th century Europe and later utilized by the French Resistance during World War II. The original seven founding members were in level five and newcomers in levels one and two, not knowing who was in the level above them.

By late 1952 and early1953, however, Mattachine had created close to a hundred discussion groups in California with about two thousand participants—a stunning achievement for the early 1950’s — and was evolving into a more grassroots organization with a wide range of people with varied backgrounds and political views—largely men—in attendance.

Then in March 1953 all hell broke loose when Paul Coates, a popular newspaper columnist, reported publicly for the first time the existence of Mattachine and the ties of some of its organizers to the Communist Party (I speculate he was tipped off by the FBI).

The Homophile Period (1953-1969): Conservativism, Respectability and Assimilation

The heretofore unknown Coates revelation, during a period of fanatical anti-Communism in the U.S., threw the Mattachine into turmoil and the seven, secret level five leaders unmasked themselves. In the Spring and Fall of 1953, emergency meetings of Mattachine were called in L.A. and a quick conservative and ideological coup took place. The original seven founding members either eventually resigned or disappeared. Their early organizing efforts and attempts at political and cultural consciousness-raising seemingly eradicated by the conservative coup-makers.

The leadership of the anti-Communist “Second Mattachine,” as Hay called it, moved to San Francisco and by 1969 had dissolved into nothingness.

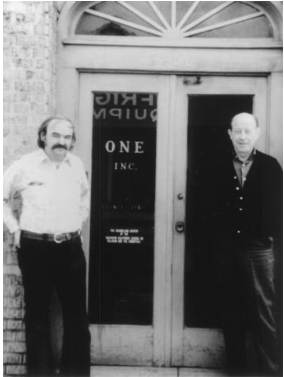

In Los Angeles, ONE, Inc. (a name derived from Thomas Carlyle’s “A mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one”) replaced Mattachine and started using the descriptive term “homophile” (lover of man or same), importantly broadening identity from a solely sexual definition to also include relationship.

As Mattachine had started homosexuals talking to each other about their oppression, albeit secretly, the Homophile era was important in that, through its pioneering publications, the written word also came out of the closet for the first time. In a 1958 landmark legal case initiated by ONE, the U.S. was forced to allow these publications to be sent through the mail, an important breakthrough that allowed greater intracommunication that gradually caused ripples to go out across the country.

Leaders during the Homophile period, predominantly centered in Los Angeles, were largely conservative Republicans. Homophiles propagated an assimilation/sexual orientation ideology of identity. For them, assimilation meant homosexuals needed to adjust to the dominance of heterosexual culture, institutions, and social norms, which they believed would lead to social acceptance. It did not. In addition, the “sex variant is no different from anyone else except in the object of his sexual desire” as one of their founding documents put it.

Additional defining characteristics of the Homophile era included denying that a homosexual culture existed, law reform was a panacea, advocates for social acceptance for homophiles should not be homophiles themselves but hetero professionals (ministers, attorneys, psychologists and psychiatrists), and, for safety purposes, pseudonyms were widely used to shield real identities.

The best account of the Mattachine and Homophile periods is gay historian John D’Emilio’s “Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970. “

D’Emilio, looking back over the attempted erasure of Mattachine and the ascendency of the Homophile effort, writes, “In sum, accommodation to social norms replaced the affirmation of a distinctive gay identity, collective effort gave way to individual action, and confidence in the ability of gay men and lesbians to interpret their own experience yielded to the wisdom of the experts.”

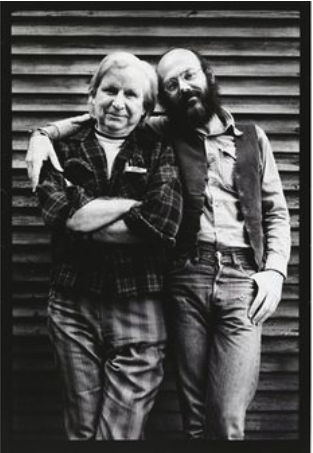

I bow with great respect and deep appreciation in the direction of those of both the Mattachine and Homophile efforts. I knew several of their leaders personally and two elders from that period—Hay and Jim Kepner—transmitted the history of the era to me directly.

The Gay Liberation Period (1969-circa 1990): The Radical, Grassroots “Big Bang”

On June 28, 1969, at a Mafia-owned dive in New York City, a global social revolution of major proportions was launched, and the lives and well-being of gay and lesbian people in the U.S. changed forever. It is called the Stonewall Rebellion (or “riots” by more conservative people).

It is important to understand historically that in New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco and elsewhere the seeds and inspiration for the early Gay Liberation revolution did not come from either the Mattachine or the Homophile efforts, whose history most people were unaware of, even many members of the Gay Liberation Front of Los Angeles (GLF), in whose city that history resided.

Gay Liberation was seeded largely by the inspiration of and modeling by the bravery of lunch counter sit-ins by black college students, water hoses and the militant black civil rights movement, the in-your-face anti-Vietnam War protesters, early feminist thought and action, and the righteousness and zeal of numerous other social justice/social change movements.

Before Stonewall, many gay and lesbian people were actively engaged in a myriad of progressive social change efforts, sometimes in leadership positions, but in the closet due to the virulent and institutionalized hetero supremacy in progressive circles and society in general. After Stonewall, a handful of those activists-in-other-causes, like 28-year old me, began to see our own personal fight for freedom as a gay person as well as the Gay Liberation movement itself as an essential part of the social revolution occurring around us.

The word “gay,” a mid-20th century in-word increasingly used by hip folk that was gay-derived and into which a new gay-defined and gay-defiant identity could be poured, was married to the word “liberation.”

In Los Angeles and throughout the country during the Gay Liberation period, actualizing self-respect replaced the courting of acceptance by the respectability agenda of the Homophile period. A Homophile emancipation mind-set (heteros will give us our freedom and accept us if we behave and act just like them) was superseded by a liberation ideology and a grassroots, radical protest movement (gay and lesbian people will unite collectively and militantly free ourselves). It worked.

In L.A., GLF, the central organizing entity facilitating the Gay Liberation movement here, fought back against hetero supremacy with direct confrontational political action and a fierce unwillingness to compromise on anything impacting the freedom and well-being of gay and lesbian people. Gay Liberation was engaged in something much larger than individual selves—the liberation of a people—and those involved were transformed by the process and transformed others. After a year and a half of audacious demonstrations and confrontations, in 1971 GLF’s Gay Survival Committee morphed into the Gay Community Services Center (now called the LA LGBT Center) around which an organized, visible and politically proactive gay community coalesced where none had ever existed before. By the end of the 1970’s, the Center had grown into the largest organization of its kind in the world, a well-earned distinction it still holds.

For the first time in gay history in L.A., Gay Liberation also supported and allied itself with other militant, community-based efforts (black, latinx, Asian, first nation, poor, civil rights, anti-war) that supported us. Not only gay freedom and community-building motivated GLF, but also the restructuring of U.S. society to ensure equal opportunity and a reinterpretation of American history to include all those written out of that history were part of its agenda.

In the late 1970’s I talked Hay into returning to L.A. from psychological exile in New Mexico and in 1979 literally moved him back—the Mattachine and Gay Liberation historically united in co-creating another leap forward in gay-centered consciousness, the Radical Faeries. Hay experienced a renaissance in his life.

The Neo-Homophile Period (circa 1990-present): A Retreat To Respectability and Assimilation Again

The term “Neo-Homophile” is a name that easily identifies the current political and cultural period.

With the introduction of protease inhibitors in the 1990’s, the worst of the AIDS pandemic, a gay community and global nightmare, began gradually to recede in the U.S. A new period in L.A gay history, which had emerged slowly during the 1980’s, began to reveal itself in full.

The grassroots community-building and the assertive, more or less unified, collective political activity of Gay Liberation gradually died away. A robust gay social change movement ceased to exist in L.A., being replaced instead by a party—both of the Democrat Party variety and in a more commercial WeHo Pride sense. The community changed from having participants to being spectators.

While the contemporary Neo-Homophile era is without doubt many steps higher on the political and cultural evolutionary ladder than its pre-Stonewall namesake, the two eras have a basic resonance with each other, even though there is no strict one-to-one correspondence.

The name fits because today the Neo-Homophile’s underlying political, personal identity, and cultural consciousness resembles the earlier conservative Homophile era, but with a liberal, public relations veneer.

Currently there is the same Homophile assimilation ideology (we are no different than heteros except for the object of our sexual desire) with a largely white, upper middle-class agenda, often imitating and conforming to hetero culture—for example, marriage, which fails about 50% of the time and which was low on Gay Liberation’s agenda.

James Baldwin, our Black, gay brother, warned us, that “whenever a minority assimilates into the dominant culture, it always does so totally on the terms of the dominant culture.”

Another characteristic of the Neo-Homophile era is its top-down, hierarchical structure largely based on race, class, wealth and a mildly- reformist agenda and conventional electoral politics. It is why the grassroots Spring 2020 Insurrection, triggered by police violence toward black people, befuddled Pride and the West Hollywood Neo-Homophile establishment, causing a debacle there.

Now, the continuing tug-of-war between Christopher Street West and the City of West Hollywood, acting as if each entity owns Pride, and as if the opinion of the Los Angeles LGBTQ community is irrelevant, demonstrates how far Neo-Homophilism has drifted from the idealism of Gay Liberation and how impervious it has become to real social change.

In the process, the promise of Stonewall and the meaning of community are being recklessly and irresponsibly distorted beyond recognition by the Neo-Homophile power structure. Trust has been betrayed.

The Gay Liberation period was centered mainly along the North Hollywood-Hollywood-East Hollywood-Silverlake-Echo Park axis, areas more representative of the heterogeneity of the community, albeit very imperfectly. Neo-Homophilism in L.A. today is almost totally represented by the out of touch with the larger community “WeHO Bubble”—white, wealthy, privileged and monocultural. Seventy percent of L.A. residents are now non-Caucasians; on the WeHo island only 18% are non-white, 3% black.

A final characteristic of the Neo-Homophile era is that it is largely accommodationist and collaborative with the current economic structure and class system in the U.S.

While many Gay Liberationists called for a restructuring of society to include economic fairness, equality of opportunity, and broader inclusion of everyone, the rainbow capitalism of the Neo-Homophile period largely focuses on securing larger and larger slices of the money pie with no collective advocacy for larger structural changes that would benefit everybody, particularly ordinary LGBTQ frontline working people.

The important Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling giving LGBTQ workers legal protect surprised most gay people because workers’ rights and well-being are not high on the Neo-Homophile agenda.

Prologue

After reading this essay, it should be easy to connect the historical dots. My rich imagination and abundant altruism, however, envision a fifth historical period.

A Forward Vision — The Queer Liberation Period (2020-2050): A Revolution in Political Consciousness, Community and Identity

As a result of the Black Lives Matter Rebellion in May and June 2020, fueled largely by young people, the L.A. LGBTQ community awoke from its Neo-Homophile slumber. A younger generation of leadership emerged, representing all the colors in the rainbow and socioeconomic possibilities. A political and cultural sea change took place.

The Queer Liberation period was characterized by a new, radical political consciousness, modeled by BLM, in which the wimpy, psychological nomenclature, “homophobia,” of the mid-20th century was replaced by a more societally astute, 21st century understanding of queer oppression by their adoption of the term “systemic and institutionalized heterosexual supremacy”—”hetero supremacy” for short.

The word “queer,” which in the early 21st century had an amorphous, superficial quality to its usage, was infused by Queer Liberation with powerful political and cultural meaning that carried forward-moving gravitas and the smell of revolution.

Concrete demands were made on the political system at all levels based on the real needs of gay and lesbian people—affordable housing, decent paying jobs, accessible quality education, affordable health care—rather than the photo-ops of Neo-Homophile politicians and their sycophants, and being a cash cow for both political parties.

A keen desire arose for older forms of participatory community. Politically aware, queer young people and others, active in social change movements elsewhere, returned to queer community organizing, creating a community ethos that called for assuming responsibility for each other, meaning everyone—a community where, as John Lewis put it, “no one will be left out or left behind.”

Age-apartheid gradually died out and vital intergenerational dialogue and cooperation thrived between the Queer Liberation generation and those that went before. This benefitted Queer Liberation because they knew from dialogues with their elders not to become distracted by white racist tokenism and by the hollow lip service of corporations and politicians who claimed verbally to support critically needed, structural changes in society. Queer Liberation kept its eye on the prize. Their only litmus test for “the talkers” was that their lips and feet moved in the same direction.

Historians dubbed the queer era as “a renaissance of queer- centered community building”—new community-based institutions and cultural venues thrived. The mass entertainment, rainbow credit cards, and shallow celebrity culture of the Neo-Homophile era faded away.

In L.A., a new generation built the world’s first Queer Community Cultural and Performing Arts Center, which became a generator of queer creativity and an exciting model for communities globally.

After years of militant attacks and confrontations by Queer Liberation, the Catholic Church was forced to rescind its dogma that queer people were “intrinsically morally disordered,” a victory as important as Gay Liberation’s 1973 victory over the mental health industry.

Shortly thereafter, Pope Francis and 16 Cardinals announced publicly they were queer. Other religions followed close behind, apologizing for the grave violence and harm their teachings had caused.

A queer community mosque, where everyone was welcomed, opened in South L.A. led by a queer imam. In North Hollywood, a Hindu temple flourished with truly queer priests and spirit-intoxicated queer youth danced in ecstasy rather than on it. Queer drumming circles facilitated shamanic healing ceremonies all over the city aimed at maintaining the spiritual health and well-being of the queer and larger community.

Community alliances were made with other militant social change and progressive efforts in the U.S. that ended thirty years of Neo-Homophile insularity. At the same time Queer Liberation also became a dynamic and militant international movement with important political and cultural breakthroughs around the world led by local queer leaders and communities, particularly in China, Russia, Africa and the Islamic world. No queer person anywhere was alone anymore. Being queer was no longer a death sentence.

After clawing it away from West Hollywood, WeHo Pride was reclaimed by the community and became a Los Angeles-based, grassroots Queer Freedom Day march again. Due to an expansive and inclusive political queer consciousness, the march was relocated to DTLA—the center of L.A. where East meets West and North meets South—and floats honoring Stonewall and noteworthy ancestors replaced anachronistic corporate ones.

During the Queer Liberation era, the visual culture hamster-wheel slowed down enough that face-to-face queer history and culture courses flourished in the community and an intellectual awakening occurred. Intelligent, young queer people no longer had to dumb it down to be accepted in the community. Queer visual and literate cultures became a both/and reality.

As a result of this intellectual awakening and widespread Queer Liberation consciousness-raising, the outdated assimilation/sexual orientation model of identity was replaced by a deeper, contemporary, existential understanding shaped by queer empirical experience and corroborated by evolutionary- and socio-biology. It was called an essentialist/social contribution model of queer identity.

Echoing through all the stages of this history, the words of Martin Luther King, Jr., ancestor of all, were never forgotten, “It was a struggle yesterday, it’s a struggle today, it will be a struggle tomorrow, and, if it’s not a struggle, you’re doing something wrong.”

__________________________________________________________

Part II of this essay, titled “Understanding the Rewriting of the History of Gay Los Angeles: Moral Integrity and Historical Honesty” will appear shortly.

[…] The early vehicles for this radical revolution in L.A. were the Metropolitan Community Church and the L.A. Gay Liberation Front which evolved into the Gay Community Services Center (now the LA LGBT Center), then as now, the largest such organization in the world. (“Understanding LA Gay History”) […]

[…] The early vehicles for this radical revolution in L.A. were the Metropolitan Community Church and the L.A. Gay Liberation Front which evolved into the Gay Community Services Center (now the LA LGBT Center), then as now, the largest such organization in the world. (“Understanding LA Gay History”) […]

Kudos to Don for providing a positive vision for the LA Queer community’s future in the post-West Hollywood era.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2kApC5rioUM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8cja67opz4Q

A point of view from an admirable and authentic person who advocates…..”it is not what you are but who you are”

An excellent documentary produced by Patrick Dempsey.

The beauty is that we all get to be individuals and not be treated as a monolith in which there are standards police and thought monitors and spokespeople to decide what words and what actions we individually need to take, or how we dress, or how we interact, or how we choose to be proud. We all get to decide if we choose to marry, or not. We all get to decide if we choose to identify as gay if that’s our choice, or queer, or lesbian, or whatever moniker one chooses. We have never been a monolith, and that’s… Read more »

Great story. When I first moved to West Hollywood in 1997 I wouldn’t even put the West on my return address because I didn’t want people to think I lived in the gay part of L.A. People would yell “F@**0!” out of the windows of their cars and us on the sidewalk every Saturday night that I went out on Santa Monica. But in that strange way, I miss that time because it was edgier. Assimilation is safe, but boring. It’s probably for the best for the younger generations. Normal is healthier, if less stimulating. Pride should not be for… Read more »

Hi Don- Thank you for sharing your bird’s eye view of the evolution of gay organizing in Los Angeles, and for your inestimable contributions. I too hold your hope of an increased inter-generational dialogue and actively seek out those moments, such as now! Regarding same-sex marriage our thoughts diverge. I believe that everyone should have the option of marrying the consenting adult of their choosing, without fear of being denigrated as assimilationist. Many gays and lesbians want to marry someday- great! Many don’t- great! They now get to decide for themselves, versus having that decision preordained. And many that opt… Read more »